The idea of India is ancient, not necessarily reflected in the statute books of today’s Anglicised India, but perhaps in the underlying socio-cultural context that forms the civilisational backbone of Bharat or Hindusthan and, therefore, reflected also in our existential ethos. It is because of this heritage that the founding fathers of our Constitution had not felt the necessity to incorporate the word ‘Secular’ in our Constitution or define ‘Minorities’, as those were not commensurate with the very cultural fabric of our ancient land, despite the Constitution having being drawn up in the backdrop of a painful and bloody division of Hindusthan based on religious intolerance back then. Inevitably, arising from long colonial rule and a skewed education system, certain discrepancies had inadvertently crept in while framing the Constitution of a newly divided India or even later, which now needs to be addressed and amended.

Dr. Kesav Baliram Hegdewar, the founder of RSS had stated in it’s mission statement, “The Hindu culture is the life-breath of Hindusthan. It is therefore clear that if Hindusthan is to be protected, we should first nourish the Hindu culture. If the Hindu culture perishes in Hindusthan itself, and if the Hindu society ceases to exist, it will hardly be appropriate to refer to the mere geographical entity that remains as Hindusthan. Mere geographical lumps don’t make a nation.” Needless to say, our Statutes must reflect this ancient pluralistic culture of ours in letter and spirit. We shall today review the provisions made under Articles 26-30 in the Constitution of India in that light.

Let us begin by saying that the secularism of the West is alien to India. For them what is tolerance for all beliefs and faith, is for us respect for all faiths and beliefs. While the West propagates complete separation of the State from the Church or Religions, our Constitution must reflect not mere separation from Religions but adherence to the principles of Dharma, our ancient moral law that has governed our society through the ages. However Articles 26-30 of our Constitution imply that we have forcefully tried to imbibe an alien concept of secularism and in our pursuit to create equal rights and opportunity for all, we have created special rights and opportunity for some. Articles 27, 28 and 30 contain some specific provisions, as also other provisions elsewhere in the Constitution of India, which do not subscribe to complete separation of the State and Religion. Moreover, all these provisions are skewed positively towards religious minorities, and all those believing in the Sanatana Dharma, irrespective of their belief in different Religions or Sects within that broader ambit, have been classified as religious majorities and left out of specific rights and opportunities given by these Articles, which requires urgent course correction.

Let us first quickly recall these Articles. Article 26 guarantees to every religious denomination, or a section of it, a right to manage its own affairs in matters of religion and the right to establish and maintain institutions for religious purposes. Articles 27 provides that no person shall be compelled to pay any taxes, the proceeds of which are specifically appropriated in payment of expenses for the promotion or maintenance of any particular religion or religious denomination. Article 28 keeps religious instructions out of public education system in the country. Article 29 confers cultural and educational rights to all sections of citizens, majority or minority, having distinct language, script or culture of their own. Article 30 upholds the right of only the minorities “to establish and administer educational institutions.” If we go through the provisions of these Articles one by one, we would understand how these are discriminatory towards the followers of the Sanatana Dharma and therefore is indicative of a non separation of State and Religion in the true sense of the term. It is interesting to note that during the debate regarding these Articles in the Constituent Assembly, on 7th December 1948 Syed Abdur Rouf (Assam) said something which is self explanatory:

“That in clause (a) of Article 20 [corresponding to the present Article 27], for the words `religious and charitable purposes’, the words `religious, charitable and educational purposes’ be substituted. We are dealing here with a subject which empowers religious denominations to have the right to establish and maintain institutions for religious and charitable purposes only. Religious education is as important as religion itself. Without religious education the charitable purposes or religious purposes would lose all meaning. Therefore, I hope my amendment would be accepted by the House.”

It has now been established through various judgments that three conditions must be satisfied in order to qualify as a religious denomination under Article 26. These are:

- It must be a collection of individuals who have a system of beliefs which they regard as conducive to their spiritual well-being, i.e., common Faith

- Common Organisation

- Designated by distinctive name

Therefore, members belonging to different religions, satisfying the three tests, would be a denomination within the meaning of Article 26. The expression ‘denomination’ can also be used for members forming sects or sub-sects of a religion designated by a distinctive name. It is pertinent to note that, unlike Article 30, benefit of Article 26 is not confined to ‘minority’ groups only. Sikhs, a majority in Punjab, constitute a ‘religious denomination’ and can thus, claim the benefit of Article 26. However, successive rulings in Courts have established that the same rights are not to be enjoyed by The Ramakrishna Mission, The Brahmo Samaj and the Arya Samaj as Hindu sub-sects, indicating non-universalisation of the dictum. If we go into further details, under Article 26(a), a denomination has no right to maintain an institution until and unless it has not been established by it, whereas that the term ‘matters of religion’ used in Article 26(b) is synonymous with the term ‘religion’ in Article 25(1) and it includes not only religious beliefs but also such religious practises and rites as are regarded to be an essential and integral part of religion. The grievance lies in practical discrimination while administering Article 26(b) and 26(d), as regards administration of property which a religious denomination is entitled to own and acquire. The State has undoubtedly the right to administer such property but only in accordance with law, meaning thereby that the State can regulate the administration of trust properties by means of laws validly enacted. We have observed that Hindu temples and religious and charitable institutions have routinely been taken over invoking this Article by the State whereas mosques and churches have largely remained untouched. There is also large scale dissatisfaction arising out of arbitrary implementation of The Hindu Temple and Religious Endowments Act, whereby incomes and properties of temples are misappropriated and redirected for non Hindu purposes by the State resulting in acute poverty and state of disrepair for Hindu temples, priests and their families. This Article needs amendment regarding management of Hindu temples and religious endowments to make its administration non selective, non discriminatory and unbiased.

Coming to Article 27, a tax is a common burden which results in common benefit whereas a fee is a payment for some special services rendered for the benefit of those for whom the special service has been provided. In the Jagannath Ramanuj Das vs. State of Orissa (1954) case, The Supreme Court had held that as per the Orissa Hindu Religion Endowments act 1939, the annual contribution imposed on every Math having an annual income exceeding Rs.250 towards meeting the expenses of the Commissioner, the officers and servants working under him was a fee and not a tax.

However, later, the Supreme Court while considering the Constitutionality of the Government of India’s granting subsidy in the air fare of the Haj pilgrims, specifically in the context of Article 27 of the Constitution of India, had rejected the challenge and observed as follows:-

“In our opinion Article 27 would be violated if a substantial part of the entire income tax collected in India, or a substantial part of the entire central excise or the customs duties or sales tax, or a substantial part of any other tax collected in India, were to be utilized for promotion or maintenance of any particular religion or religious denomination. In other words, suppose 25 per cent of the entire income tax collected in India was utilized for promoting or maintaining any particular religion or religious denomination, that, in our opinion, would be violative of Article 27 of the Constitution”. (Dr.Surbahmaniam Swamy vs State Of Kerala on 27 January, 2011).

It must be kept in mind that discrimination on religious lines creates disharmony and dissatisfaction in the society. The State has to be fair and truly secular and collection and utilisation of funds must be based on principles of equality. It is the duty of the State to ensure that no moneys out of the Consolidated Fund of India, the Consolidated Fund of a State or out of fund of any Public body shall be appropriated for advancement or promotion of a section of citizens solely or primarily on the basis of their religious affiliation or language. Language as a primary or sole consideration must also be excluded from State funding as certain languages have exclusive association with certain religions which may be used to circumvent the purpose of the proposed inclusion of the above as a clause in Article 27.

In 1966 in the famous Sastri Yagnapurushadji case a five Judge Bench of the Supreme Court had observed: “When we think of the Hindu religion, we find it difficult, if not impossible, to define Hindu religion or adequately describe it. Unlike other religions in the world, the Hindu religion does not claim any one prophet, it does not worship any one god, it does not subscribe to any one dogma, it does not believe in any one philosophic concept, it does not follow any one set of religious rites or performances, in fact, it does not appear to satisfy the narrow traditional features of any religion or creed. It may broadly be described as a way of life and nothing more.” [1966 SCR(3) 242]

When we read Article 28, we find that it rightly keeps religious instructions out of the public education system but Hinduism being a way of life and not a religion per se, must not be allowed to be brought under the provisions of this Article. Infact, on the contrary, our traditional knowledge systems and civilisational heritage in the form of our ancient texts like the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Upanishads, the Vedas etc. must be at the core of our public education system. Generations cannot and must not be kept away from their civilisational and socio-cultural inheritance and, therefore, a provision in Article 28 needs to be added by way of an amendment thus: “Nothing in the Constitution shall be deemed to forbid the teaching of traditional Indian knowledge or ancient texts of India in any educational institution, wholly or partly maintained out of State funds.”

Now, we move on to Article 29. The first part of the Article relates to only minorities, which is somewhat discriminatory and partial. The Article reads:

Protection of interests of minorities:

(1) Any section of the citizens residing in the territory of India or any part thereof having a distinct language, script or culture of its own shall have the right to conserve the same

(2) No citizen shall be denied admission into any educational institution maintained by the State or receiving aid out of State funds on grounds only of religion, race, caste, language or any of them

Had it read “Protection of interests of cultural and educational rights” instead of “minorities”, both 29(1) and 29(2) would have had a much broader and equalitarian connotation. While 29(1) gives an absolute right only for the minorities to preserve its language and culture through educational institutions and cannot be subject to reasonable restrictions in the interest of the general public, 29(2) is an individual right given to citizen and not to any community in particular. This leads us to the definition of minorities, which the Constituent Assembly chose to avoid and left it to the wisdom of the Judiciary.

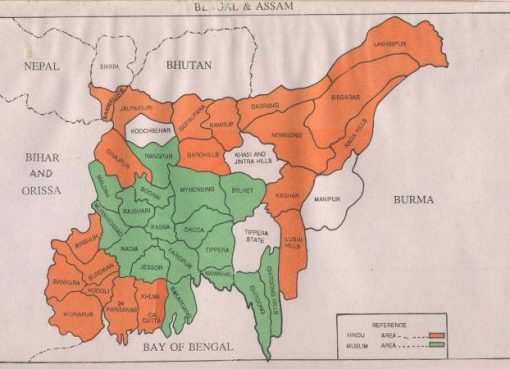

Searching for definition of Minority under the Constitution while Article 23 of the Draft Constitution [corresponding to the present Article 30] was being debated, doubts were indeed expressed in the Constituent Assembly over the advisability of having vague justifiable rights to undefined minorities. The opportunity arose in 1959 in re. Kerala Education Bill 1957, where the Supreme Court through Chief Justice S.R.Das, while suggesting the technique of arithmetical tabulation, held that a minority means a community which is numerically less than 50 per cent of the total population. The Court held that when an act of a State Legislature extends to the whole of the State, the minority must be determined by reference to the entire population of the State and any community which is numerically less than 50 per cent of the entire State population may be regarded as a minority for the purpose of the Constitution. The judicial opinion of application of two tests – statistical and geographical to determine the minority status of any group is not beyond question as what is minority in one part of the country is not a minority in another.

This brings us to the last section of our present discussion, that regarding Article 30. Article 30 is classified under Part III of the Indian Constitution that elucidates all the Fundamental Rights guaranteed to the citizens of India irrespective of their religion, caste and sex. Article 30 upholds the right of the minorities “to establish and administer educational institutions.” In re. Kerala Education Bill 1957, S.R.Das, C.J. had observed that “the key to the understanding of the true meaning and implication of Article 30 are the words of ‘their choice’ and that the choice and the content of that Article is as wide as the choice of the particular minority community may make it.”

Besides safeguarding the rights of religious and linguistic minorities to establish educational institutions of their choice, the Article categorically directs the government to ensure that the minority rights do not get abrogated in case of compulsory acquisition of educational institutions run by minorities. To make sure that acquisition of minority institution should be followed by ‘conformable compensation’ clause (1A) was inserted in the Article during the 44th amendment of the Indian Constitution in 1978. In reality Article 30 gives minorities the right to ‘administer’ educational institutions where the government has no right to exercise any control on the formation and management of the governing body and even in case of ‘gross malpractice’, the government cannot intervene and take charge. Article 30(1) virtually exempts minority institutions from the obligation of implementing the reservation policy for backward castes. This is in sharp contrast to other Articles that provides reservations for backward classes. Article 30 also exempts unaided minority institutions from reserving 25 percent seats for the poor, as is mandatory under the Right to Education Act for educational institutions, shifting the onus of education for all only on majority run educational institutions.

Although the intention of Article 30 was to ensure that minorities are not denied equal treatment, in reality, it is seen as a legislation that denies non-minority the right to “establish and administer” their institutions their way. Article 30 actually divides the country on religious lines since institutions run by the Hindus suffer government intervention, while minority educational institutions enjoy complete autonomy. It is evident that Article 30 protects the rights of the few and deprives the majority. The developments in the recent past indicate a possibility of communal imbalance being aggravated as many institutions have started claiming minority status purely for the sake of benefits they can avail.

Ironically, in the St. Xavier College vs. State of Gujarat case, it was said, “the spirit behind the provision of the following article is conscience of the nation that the minorities, religious as well as linguistic, are not prohibited from establishing and administering educational institutes, of their choice for the purpose of giving their child the best general education to make them complete man and women of the country.” It would have been far more inclusive and far more secular if the scope of Article 30 was broadened to include all communities and sections of citizens who form a distinct religious or linguistic group to meet the aspirations for conserving and communicating religious and cultural traditions and language for succeeding generations. An eleven Judge Bench of the Supreme Court had said in the T.M.A. Pai Foundation vs. State of Karnataka, “The right to establish and maintain educational institutions may also be sourced to Article 26(a), which grants, in positive terms, the right to every religious denomination or any section thereof to establish and maintain institutions for religious and charitable purposes, subject to public order, morality and health.” It is imperative that the word “minorities” be replaced with “all sections of citizens, whether based on religion or language” everywhere for the Article to become representative of the true nature of our democracy, that the State has no religion and treats all religions and religious people equally and with equal respect, without in any manner interfering with the right to freedom of religion, faith and worship. Ideally, Article 30 should be substituted as per the bill brought by Syed Shahabuddin in the Lok Sabha on April 20, 1995 (bill no.36 of 1995) that began thus: 30(1) Any section of the citizens residing in the territory of India or any part thereof professing a distinct religion or having a distinct language, script or culture of its own or forming a distinct social group shall have the right to establish and administer educational institutions of its choice.

The time to amend the Constitution of India and make it unbiased and non-discriminatory towards the Hindus is ripe. Laws are meant to be changed with time, and they should forever reflect the mood of the nation. Those tumultuous times of partition are far behind us and we must now go back to our civilisational roots, to our ancient Dharma which announces unequivocally that, “May all be happy, May all be healthy, May all see auspiciousness everywhere, May none ever feel sorrow and May there be Peace Peace Peace.”

(Written in support of Bill No.226 of 2016 by Dr.Satya Pal Singh, M.P.)

রাজনৈতিক বিশ্লেষক, চিন্তাবিদ এবং সমাজকর্মী

Comment here

You must be logged in to post a comment.