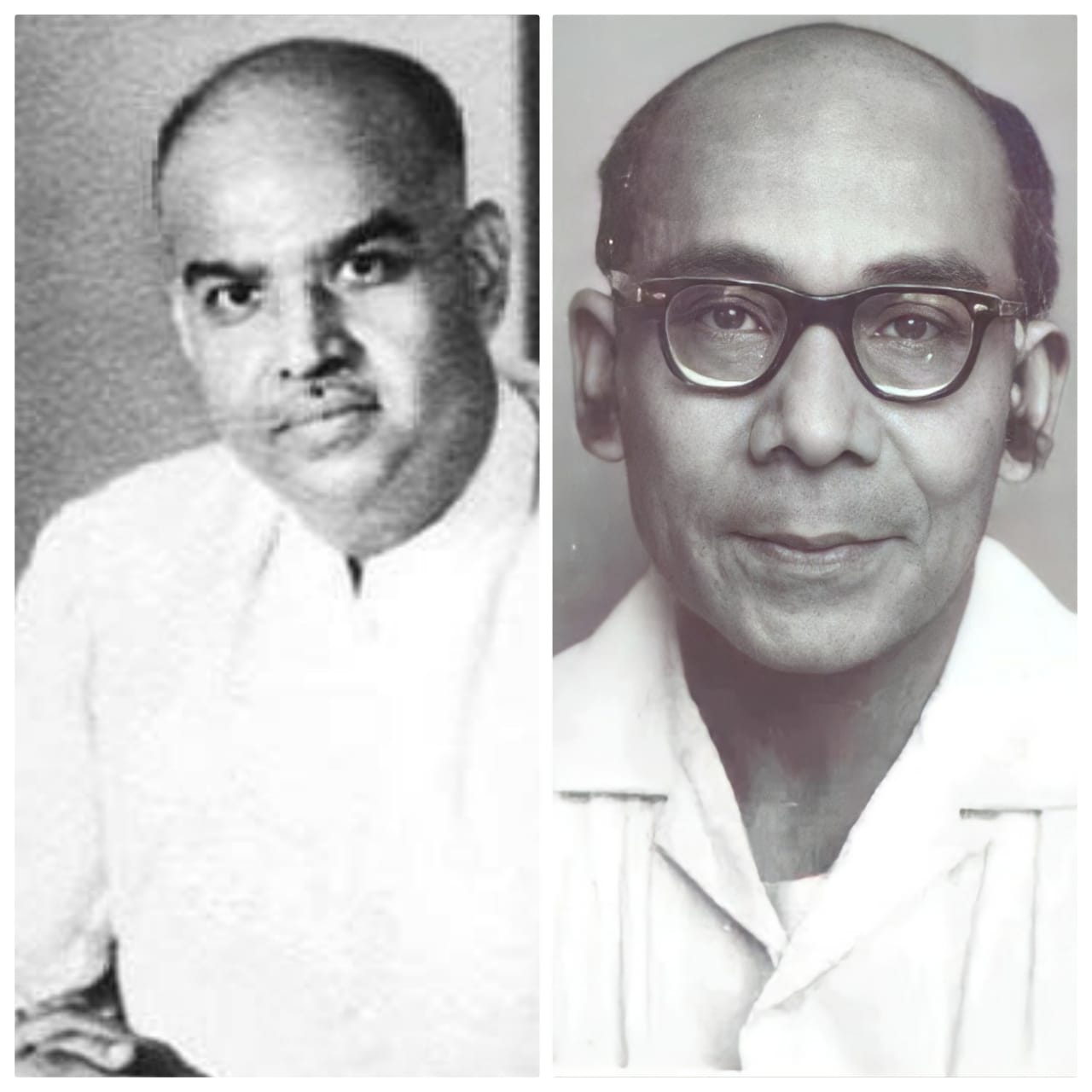

—Hiren Mukerjee

“Let us praise our famous men” is a scriptural injunction, and it is in any case a pleasure and a sort of pious obligation to remember and salute an outstanding public figure and par- liamentarian, Syama Prasad Mookerjee, whose premature death in 1953 left a void that could not be filled.

Son of the great Asutosh Mookerjee who built, in 1917, the post graduate departments in Calcutta University and did, more than any one person to put India, as it were, on the research map of the modem world, Syama Prasad had some built-in advantages, but he justified by his talent, his induction in the University’s Syndicate as its youngest ever member. When, later in his early thirties, he became India’s youngest Vice- Chancellor, he proved again that the honour had been his by dint of merit. With his wide interests he was drawn into public life and in spite of the inhibitive atmosphere of pre-independence India he made his mark in the limited, but often brilliantly functioning legislatures of the time. In the early forties, it was felt to be in the fitness of things that Syama Prasad Mookerjee was a Minister in the government of the then undivided province of Bengal. He had his own independent bent of mind and ’it was quite in his character when in late 1542, protesting against official failure in relief operations in the stricken district of Midnapore, he resigned his office.

He had never joined the Congress, the leading party in pre- independence days, and his political views was something of a middle-of-the-road liberal, but he was drawn tocards such bodies as the Hindu Mahasabha, of which he came to be the leader. He could not, however, be glibly branded as a mere communalist, though in the heat of politics he often was. One could always discern the catholicity and also within limitations, the rationality of his outlook. There was something fine, for example, about the pride he left in Calcutta University which he for some years headed rejoicing in its department, served by notable scholars of Islamic History and culture. He cherished freedom of opinion and was as far away from socialism as one could be, but there was in him an innate liberalism which – as I remember, for example, prevent his association in late 1941 with a movement set up by some of us for friendship with the Soviet Union. He made no bones about his Hindu Mahasabha links but he was a champion of civil liberties and kept himself above the narrowness of communal chauvinism. This was testified by many who, on the communal issue, held opinions diametrically opposed to his. Syama Prasad could even make jokes against himself about this. I remember in 1952, when he and I were members together of our first Lok Sabha, he told me once: “Do you know, Hiren, they have allotted accommodation to me in ‘Tughlak Crescent’—not, mind you, in ‘Tughlak Road’ but ‘Tughlak Crescent’ and I don’t bat an eye-lid, yet some people call me a communal Hindu!“

On account perhaps of ideological as well as temperamental differences, there was between him and Jawaharlal Nehru a sort of mutual allergy. But there is no doubt about their also having a sort of mutual admiration. lt is significant that Jawaharlal could, when forming the first Cabinet of independent India, asked Syama Prasad to join and the latter also could and did accept the offer. It is a pity that differences cropped up between them over the agonizing problem of refugees from the then East Pakistan and other connected issues and Syama Prasad resigned his office and opted out of the mainstream of India’s then political leadership. By the time of the first General Elections in 1952, Syama Prasad set up his own party Jan Sangh (fore-runner of today’s Bharatiya Janata Party) which outmoded the more blatant Hindu Mahasabha. His parliamentary acumen was seen when, as ’leader’ of a virtually one-man party, he could get together a sizeable Opposition group of his own, the National Democratic Alliance.

With us, Communists, then the principal element in the Opposition, Syama Prasad maintained, in spite of basic ideological divergence, a friendly and efficient combination against the government. Over such issues as Preventive Detention for political reasons, we joined hands an with his cogent debating powers and his experience of parliamentary work, he was a remarkable figure and an asset to our public life. He was capable of giving rapier-sharp retorts. One example was when, pillorying the Government for its detention, without trial, of political opponents, he heard a voice from the government side: “Face the truth”, and his instant reply was: “How can I, for I face the treasury benches!”

It is a pity that the life of this extraordinarily capable political figure of our time was cut short early and in unhappy circumstances when he was struggling in his own way, for the full integration of Kashmir into the lndia polity. If he had lived longer, perhaps this truly eminent Indian would have made a larger and more positive contribution to our history. His personality and his pre-eminent” talents, however, should never be forgotten. Homage to his memory will come no less from those, like the present writer who have had profound differences with him during his life time.

(First published in “Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series” by the Lok Sabha Secretariat, 1990)

Comment here

You must be logged in to post a comment.